Alaska can’t afford to let oil prices determine spill prevention, by Mike Munger

Among the many lessons learned from the Exxon Valdez oil spill was that it was almost inevitable. “Success bred complacency; complacency bred neglect; neglect increased the risk—until the right combination of errors finally led to an accident of disastrous proportions.” (Alaska Oil Spill Commission 1990.)

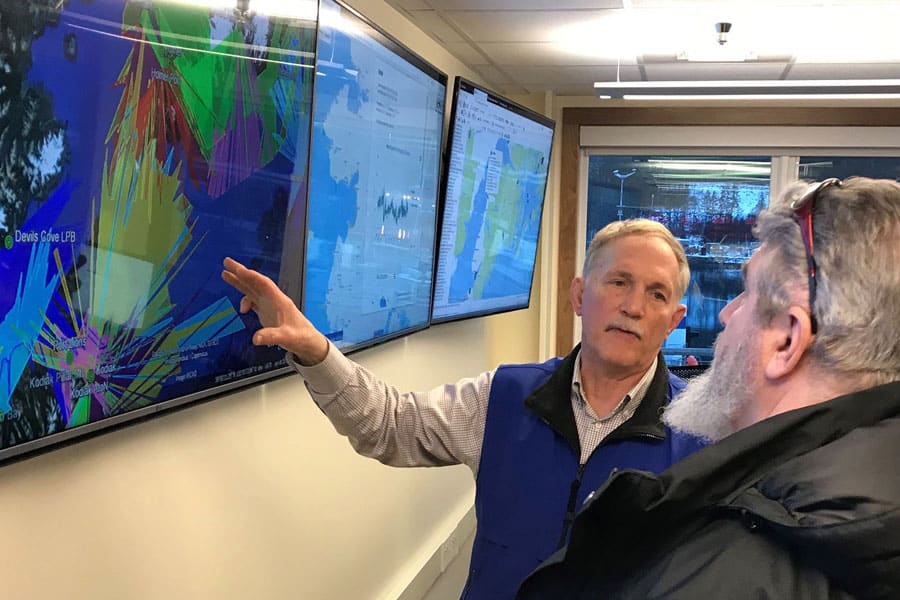

To combat that complacency, Congress created Regional Citizens Advisory Councils. As long as oil is moved, explored or developed in the waters from Cook Inlet and Prince William Sound it will be subject to citizen oversight to protect those and nearby water bodies. Congress recognized that regardless of advances in oil spill prevention and response there will always be risks.

Among the many lessons learned from the Exxon Valdez oil spill was that it was almost inevitable. “Success bred complacency; complacency bred neglect; neglect increased the risk—until the right combination of errors finally led to an accident of disastrous proportions.” (Alaska Oil Spill Commission 1990.)

To combat that complacency, Congress created Regional Citizens Advisory Councils. As long as oil is moved, explored or developed in the waters from Cook Inlet and Prince William Sound it will be subject to citizen oversight to protect those and nearby water bodies. Congress recognized that regardless of advances in oil spill prevention and response there will always be risks.

Today, massive budget cuts due to low oil prices threaten to lull us into complacency similar to that which led to the creation of the regional councils in the first place. Regulatory agencies are expected to do more with less, as some Alaskans demand budget cuts that could hamper our effectiveness in preventing and responding to a spill. At the same time, industry is motivated to cut costs through the reduction of qualified staff, reduction and consolidation of resources, and dedicating fewer staff and resources to important responsibilities.

Cook Inlet is Alaska’s first significant oil producing region and therefore the oldest. Of its 17 existing platforms, 13 were installed in the 1960s. The same is true with the onshore production and crude oil storage facilities on the Inlet’s east and west shores.

Although new technologies have allowed the oil industry to extract oil from aging fields, a combination of updated and well maintained infrastructure and adequate staffing is critical to ensure these wells, pipelines, platforms, and onshore processing facilities can continue to operate safely. While production is more automated, nothing can replace the presence of trained staff as key to safe operations.

In recent years, the Inlet has undergone a dynamic shift of major producers moving out and independents moving in. Typical of independent oil producers is a business model that includes fewer personnel compared to a major oil company. This model can fail if it lacks a strong commitment to staffing levels adequate for operations with minimal risk to human and environmental safety.

On July 2, there was a spill at the Drift River Oil Terminal, the major crude oil storage facility on the western side of the Inlet. The Cook Inlet Regional Citizens Advisory Council received the first report of a 14-gallon spill from Hilcorp Alaska along with their report of the circumstances of the discharge.

Weeks later, we received another report of 24 gallons linked to the initial incident. Both reports seemed to minimize the spill’s magnitude. After further investigation and discussions, it became apparent this spill was significantly larger than early reports indicated. The council is engaged on a daily basis with the Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation and Hilcorp to ensure the proper cleanup of the spill, which is now under investigation.

Even before this spill, the CIRAC stated specific concerns on numerous other occasions to the DEC and the U.S. Coast Guard regarding issues at the terminal. Many Alaskans recall Mount Redoubt’s volcanic eruptions in 1990 and 2009 which inundated the facility with seismic-induced mudflows or “lahars.”

Fortunate circumstances in 1990 and sound engineering in 2009 spared the terminal from any major damage, but the fact remains it is in a precarious area. The current operator has made significant strides to protect the Drift River facility from the next volcanic event. But they have also made changes that are alarming, such as an amendment to Hilcorp’s state-required Oil Discharge Prevention and Contingency Plan that reduced staffing levels. This was approved without public review or comment. We are also concerned with the frequency of comprehensive inspections and spill drills by the regulatory agencies.

Low oil prices, reduced staffing, and budget shortfalls — combined with less consistent regulatory oversight — is a bad recipe for the Inlet’s pristine environment. Rigorous regulatory oversight and oil spill prevention and response cost money, require qualified staff, and deserve sufficient resources. For the right to drill, explore or transport oil in Alaska, operators must be committed to complying with our regulations and dedicating the necessary company resources to do a proper job of it, regardless of the price of oil.

As Alaskans, we must hold industry, state oversight agencies and public officials accountable and do everything we can to prevent the unraveling of decades of progress to make oil transportation and production in Alaska’s waters safe.

The council’s goal continues to be to ensure industry compliance with state regulations. We will also continue to advocate for a well-funded state and federal regulatory regime, which reflects the shared values of Alaskans who are committed to protecting our waters, shorelines and wildlife, natural and cultural resources. Anything less is unacceptable.

Michael Munger has been the executive director of Cook Inlet Regional Citizens Advisory Council (CIRCAC) since 2003. The council is a federally mandated citizens organization, formed under the U.S. Oil Pollution Act of 1990.